Today is language arts. Specifically, the art of language. Our intrepid group of writers will be talking about Conlang: do we make up our own languages for our books? How? If not, why not?

Robin Lythgoe

Robin Lythgoe

Author of As the Crow Flies

I have a kind of lazy love for language. My copy of the 17th edition of the Chicago Manual of Style makes me crazy, but… I’m one of those readers that will highlight passages in novels that sing to me. Sometimes I copy them into a file to come back to later so I can oo and ah over them. And I did take the equivalent of seven years of foreign language in high school. (I think I learned more about English there than I did in English classes!) Then there was Tolkien. Was my experience a recipe for conlang or what?

Patricia Reding

Patricia Reding

Author of Oathtaker

“D’Abunzid Bayshofenskidoe stooped for the griggen. Past the field of hoff, ripe for picking—notwithstanding that creckenmat had only just begun, he waited for a response from Doblay Spitzen’blar.”

WHAT’S that you say???? What’s wrong? Don’t you read Mezphlatish? No problem, just check the glossary at the back . . .

I love language and the nuances communicated through highly similar but different words. I think it is fair to say that the work I do in both of my lives (as attorney and as author) depends on a keen sense of words and of the manipulation of them. For these reasons among others, I truly admire anyone able and willing to make up a language for a story and then to stick with the system religiously—which is necessary if the language is to work. If even a single instance occurs where it is not used but perhaps should have been—or perhaps could have been—then that failure could make a mockery of the entire system. But concerns . . .

Parker Broaddus

Parker Broaddus

Author of A Hero’s Curse & Nightrage Rising

Klingon. Orcish. Elvish. Dwarvish. Or even Lapine from Watership Down. They are made up languages, which raises interesting questions about the constructs of language itself. It also raises interesting questions of the creator – do you have to have an artistic bent, or a mind for engineering and constructing? And finally, how does a new language help tell a story?

I haven’t invented a language as a part of my storytelling experience. I never felt either the need or the desire. Most of the tools I needed for my particular tale already existed. But I did play with language and dialect. In A Hero’s Curse, there’s the creature that Essie names “Shuffles,” who has an unusual, fragmented style of speaking:

Tig take in a breath to hiss something back at me, but then he hears it, too. A scrabbling in the dark.

An animalistic and guttural voice calls to us from a distance away. “Wait! Theofthat good stop!” More scrambling.

And then there’s the hilarious “Chatter,” a ring-tailed cat with a stutter:

“Have no f-f-fear,” a thin voice says, “this t-t-time I’m alone.”

Since we seemed to have skipped formalities due to dragons trying to eat us, I ask the obvious question. “Who are you? And why are you following us?”

There’s a pause, and then the rodent—which does smell very much like rodent—replies, “I’m c-c-called ‘Chatter’ in Lingua Comma, and I thought you m-m-might not want to get eaten b-b-by d-d-dragons or cooked by the s-s-sun. I mean, we might d-d-die anyway, and it will probably be worse than d-d-dragons, but we can always hope it w-w-will be quick and p-p-painless.”

“Maybe we want to get eaten by dragons and cooked by the sun,” growls Tig.

The rodent, or Chatter as it calls itself, ignores Tig and speaks to me. “T-t-tell your c-cat to behave and you c-c-can come further in.”

In Nightrage Rising, a new dialect appeared. This one formed the language of an entire section of the city, and a significant portion of the story. The trick was to introduce the language in such a way the reader could immediately form a picture in their mind of the people of the Wayfair, but without slowing the story down, or, even worse, confusing the story with indecipherable linguistic acrobatics:

The heavies come stamping to a halt, breathing hard in the alley above me. My dead end. I face them as proud and defiant as I can, which is tough since I can barely stand and I’m covered in filth. As much as I wish Tig was with me today, at least he isn’t seeing this.

“You’re in tha wrong parta Plen, Missy,” growls one of the thugs, his accent thick with the Wayfair. “Bin listenin’ on tha wronga bunch. Nobody spies on tha Ratcliff gang on they’s own turf.” He pauses, apparently taking in the red bandana I wear across my eyes. “Canna believe a blind wench gave us such a run. Sorcery no doubt. Bren, get down an’ hit ‘er o’er tha head—careful if she got magic in her.”

“Blow offn. That’s a nasty spot down there. You git in tha drink and knock ‘er ‘ead.” Apparently Bren doesn’t want to get dirty. Which is ironic since I can smell them over the sewer drain.

“Carnie—you was slow at tha last killin’ job. Dinna do naw but stand and wheeze. It’s yourn turn. You get ‘er.”

Carnie responds with a rasp of steel and the chink of stone. He must be clambering down the wall into the canal. “I git ‘er boots,” he giggles.

So inventing a new language may not be my cuppa, but dialect and dialogue are favorites of mine. I absolutely love shaping dialogue with quirks and lacing it with a distinct, dialectic flavor, to give characters a unique voice. I’ve found this especially important in screenwriting, where each line has to carry so much weight and impart more than it’s share of information. A kid from the dusty streets of a tired and forgotten railway stop in the West, little more than a ghost town now, will not sound like a retired businesswoman from the busyness of the urbanized Northeastern Seaboard. They come from different worlds, and their speech, while using the same common tongue, couldn’t be more different.

I’m not so much in the game of inventing languages, as I am in understanding and imitating them.

What about you? Are you an inventor of languages? Comment below!

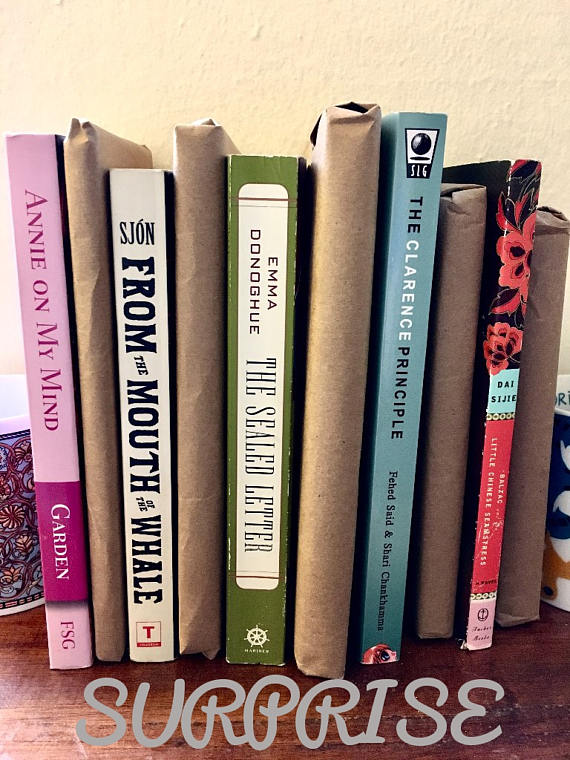

Brightsday is a 12-year-old blind girl who has a certain amount of gumption, but still wrestles to find her place in the world. The way artists and illustrators have rendered Essie is both interesting and inspiring.

Brightsday is a 12-year-old blind girl who has a certain amount of gumption, but still wrestles to find her place in the world. The way artists and illustrators have rendered Essie is both interesting and inspiring. Interesting, as each image reveals something new about both the artist and the character, and inspiring in that I get to discover new aspects to a character I created. In that respect, I love images and illustration. It adds to the story in new and unexpected ways. I get to interact with interpretations I didn’t think of.

Interesting, as each image reveals something new about both the artist and the character, and inspiring in that I get to discover new aspects to a character I created. In that respect, I love images and illustration. It adds to the story in new and unexpected ways. I get to interact with interpretations I didn’t think of. creativity to the table. And don’t we as authors want that interaction? Don’t we want readers to make the story their own? To inhabit the worlds and cherish and empathize with our characters?

creativity to the table. And don’t we as authors want that interaction? Don’t we want readers to make the story their own? To inhabit the worlds and cherish and empathize with our characters?